It is not that designers avoid images. The issue is that they don’t speak about them — particularly when compared to the attention to detail devoted to typography. Conversations about form or style are infrequent and often vague, primarily consisting of labeling as “trendy” work and designers you disapprove of.

This widespread avoidance of discussing images, form, and style prevents designers from acknowledging generational, geographical, social, or economic divisions.

However, it also discourages insights into the political aspects of design. Without dwelling on images, form, or style, political discussion remains constricted to debating whether content and context are political enough.

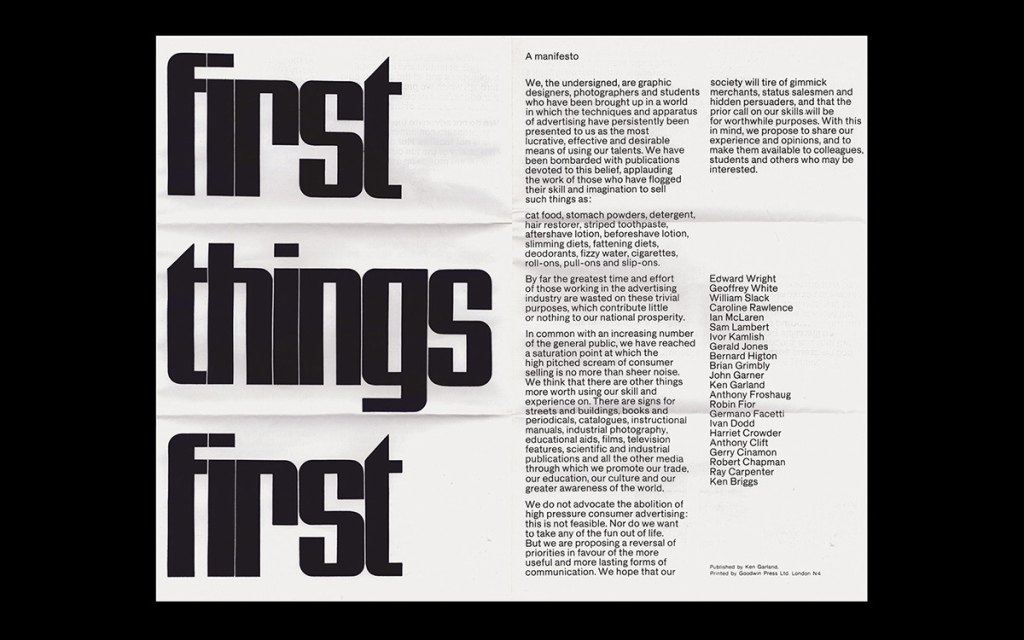

The First Things First manifestos are notable examples of this bias, where the political role of designers is limited to selecting socially worthy clients and products (such as signage and educational aids) over commercial ones (like cat food and deodorant).

Terry Eagleton’s remark about superficial Marxist literary criticism that only dwells on “how novels get published and whether they mention the working class” can be extended to political design practices and criticism that refuse to engage critically with image or form in design:

“Marxist criticism is not merely a ‘sociology of literature’, concerned with how novels get published and whether they mention the working class. Its aim is to explain the literary work more fully; and this means a sensitive attention to its forms, styles and meanings. But it also means grasping those forms, styles and meanings as the products of a particular history.” (Terry Eagleton, Marxism and Literary Criticism)

Leave a comment