This communication is about fear and response — i.e. iconophobia and iconoclasm. The starting point is online artificial intelligence tools such as Midjourney AI, Dall-e, or Stable Diffusion. These platforms generate images from natural language, the so-called “prompts,” in a “text to image” scheme.

The paper is divided into two parts. The first argues that reactions to these artificial intelligence tools are akin to iconophobia and iconoclasm. In the second part, we use this hypothesis to comment on historical situations in which people have reacted to technologies that have shaken the relationships between image and text. Finally, we use these precedents to speculate on the future of AI usage.

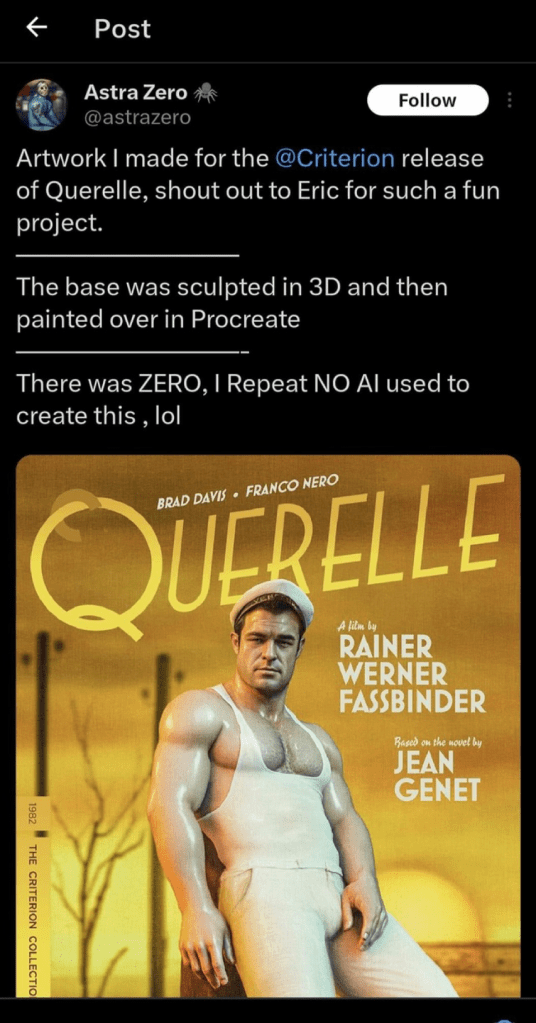

There is an undeniable risk that artificial intelligence will replace the work of artists and other professionals. However, this fear coexists with reactions of visceral repulsion, which cannot be summed up as fear of job loss and the elimination of professions. A good example is the online forums where images suspected of having been generated by AI are denounced and criticized. The expressions of disgust are extreme. The mere use of this type of AI, even when it is assumed, is considered a moral or legal failing. In some cases, even works that have not been generated by AI are accused of having been, as happened with the cover produced by the artist Astra Zero for a DVD edition of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Querelle. According to the illustrator, they used 3D modeling as the basis for a digital painting. (fig. 1) The polemic suggests that some styles become problematic because they resemble AI-generated images.

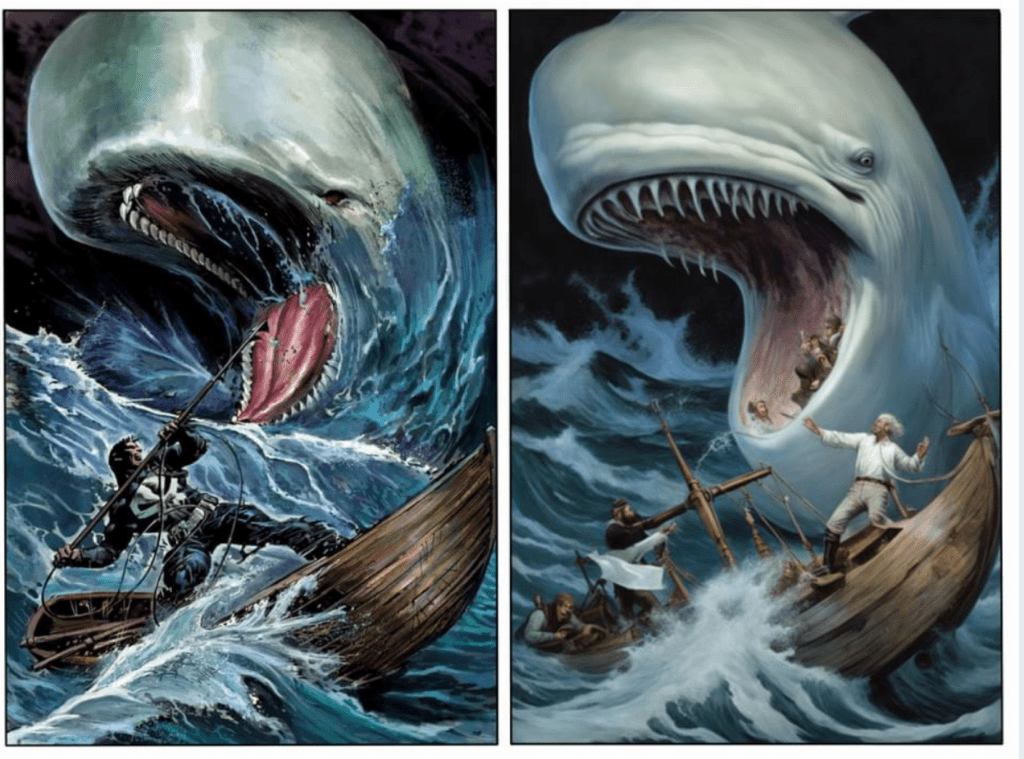

In other situations, AI is required to be more original than humans. One such case occurred in the Facebook group Comic Swipes, where instances of comic book artists referencing the work of colleagues are published and debated. In February 2024, a comparison was published between an AI-generated image and a cover by illustrators Mike Deodato Jr. and Dean White (fig.2).

Left: Mike Deodato Jr. and Dean White, 2008

Right: Unidentified A.I. , c. 2024

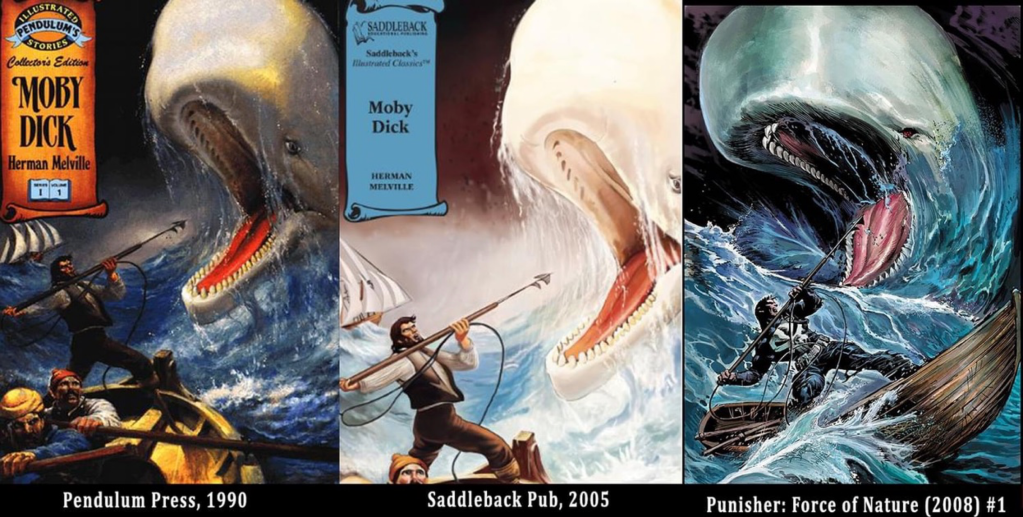

Many commentators concluded that artificial intelligence steals the work of other authors. However, these platforms generate very different images from the same prompt. The similarity between these two images probably only occurred in a few instances. It should also be pointed out that, in the same group, far more similar comparisons are published every day between works by human creators without the same degree of animosity or demand for originality. During the discussion, a commenter showed that even Deodato and White’s work was a swipe from previous illustrations (Fig. 3).

author unknown.

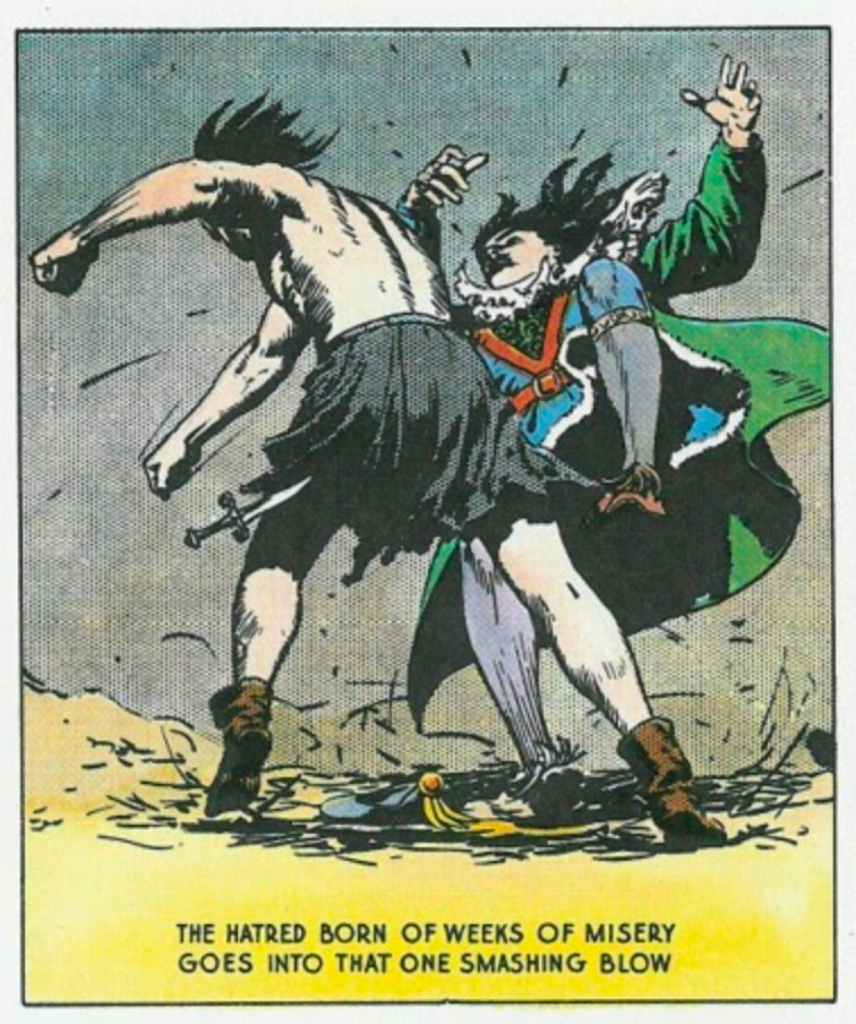

In this Facebook group, swipes between humans are considered normal unless it is a total decal. The administrators regularly expel group members who make accusations of plagiarism or express disgust against authors who swipe. Swiping is seen as integral to the artist’s normal process. Finding a swipe is uncovering a motif that connects cherished authors in a continuous thread – such as a pose originally appearing in Prince Valiant, by Hal Foster that reappears in Captain Marvel, Green Lantern, Hawkman, etc. (Fig. 4).

On the other hand, there is an extreme bias against images produced by generative AI platforms. In the Comic Swipes group, all the posts and images of this debate about AI were erased. Such censorship is standard policy in all sorts of facebook groups, where not only AI-generated imagery is banned, but also the members who post it. Iconophobia (the fear of images) and iconoclasm (the destruction and erasure of images) are usual reactions to generative AI.

In this paper, we argue that these technologies produce images and are received as images — as animated doubles with agency. We propose that how artificial intelligence is popularly perceived and discussed is similar to traditional ways of reacting to images through iconophobia and iconoclasm. The fear of animated images runs through the history of art, literature, and religion. In online discussions like the ones we’ve mentioned, images suspected of being generated by AI are subjected to aggressive criticism that aims to ban them.

For theorists like W.J.T. Mitchell, the dominant modes of criticism have an iconoclastic slant in that they dismantle images, subjecting them to the sieve of writing. The challenge for Mitchell is to produce a type of criticism that doesn’t smash idols (images) with a hammer but, inspired by a maxim from Nietzsche, makes them resonate with a tuning fork (Mitchell, 2005, p.26).

To this end, we need to be aware that, under a rationalist veneer, iconophobic reactions persist in modern times – (see (Freedberg, 1989), (Mitchell, 2005) & (Belting, 2011)). We could even add that iconophobia and iconoclasm are central to the Enlightenment project. Rationality is associated with the written word, to which the image must be subordinated. Writing implies modernity, while the image connotes primitivism and illiteracy. A person of word is reliable but a person of image is deceitful.

We need therefore to be careful: we are not arguing that reacting to these technologies as if they were images is a deception, a “step backward,” an act of “primitivism” to be corrected in the name of a deeper analysis. If these technologies offend as images, it is perhaps necessary to assume that a crucial understanding of the image is necessary, not only in contemporary society but in general. Our intention is not to devalue these reactions because they are reactions to images but to understand these responses as such. We are here in the field of what historian David Freedberg refers to as the history of the relationship between people and images (Freedberg, 1989, p. xix). It’s about studying the responses that images provoke. It’s a field of research that goes beyond art criticism but makes it possible to highlight the iconophobic contours of the critical reaction to AI and its antecedents.

Under the realization that the internet and social networks bring radically new uses and responses to images, we can see continuities between how we responded to images in pre-modern periods and places and how we interact with them in contemporary times. It can be argued that authors such as W.J.T. Mitchell, Horst Bredekamp, Hans Belting, or Victor Stoichita, use a contemporary awareness of the role of images to re-examine the pre-modern image and draw from it a knowledge that can in turn illuminate the contemporary. Against the Enlightenment idea of the image as something that entails the passivity of the viewer, an active image is re-emerging, which is endowed with agency, as can be seen in concepts such as the operative image (Harun Farocki, 2003), the networked image (Andrew Dewdney, 2021), the social photo (Nathan Jurgenson, 2019), the poor image (Hito Steyerl, 2012), or non-human photography (Joanna Zylinska, 2017).

Perhaps a parallel can be drawn between this recovery of pre-modern concepts of image and the ideas of Marshall McLuhan (McLuhan & Fiore, 1968) and Walter J. Ong (2024), who argued that one of the effects of the new communication technologies would reactivate characteristics of societies where communication was strictly oral — as before the invention of writing. When McLuhan coined the expression “global village,” he wasn’t just referring to compression of scale but to the fact that oral communication had returned, as would be characteristic of a small village. The same can be said of recovering a pre-modern way of dealing with images that are no longer just passive representations subordinated to text.

As previously said, it is not our intention to dismiss iconophobic reactions to IA as primitive and irrational. It is important to emphasize that, in addition to the problems of employment, understood only as economic issues, there is what we could call a problem of well-being or even aesthetics related to the uses of the image, which cannot be dismissed. We could perhaps recover the aesthetic and ethical notions of dignity at work put forward by John Ruskin or William Morris. Considering the image as puerile, misleading, or irrational also reaffirms a chain of hierarchy that places power on the side of the text and those who work with it.

The image constitutes a traditional frontier where questions of representation, agency, truth, and otherness intersect. The accusation of excessive faith in images is a classical libel thrown at the Other, the irrational, the illiterate, the woman, the heretic, the barbarian, or the decadent. As W.J.T. Mitchell has pointed out, «an iconoclast, in short, is someone who constructs an image of other people as worshippers of images» (Mitchell, 2005, p. 20). Iconophobia and iconoclasm emerge as modes of hierarchization that aim to restore order when technologies or social configurations emerge that blur traditional boundaries. Mitchell schematized this process as a cycle of “pictorial turns” followed by “textual turns” in which traditional hierarchies are reconstructed in a new context (ib., pp.348 – 349). New moral and taste criteria are developed, sometimes set by general law or professional ethics. The formal characteristics of transgression are in turn inscribed as bad taste, with the class implications that this entails: the supposedly “unruly and ill-informed” use of new technologies becomes a sign of lo-brow and even marginality. However, for this reason, they often turn into conventionalized representations of transgression.

This border exemplifies what Jacques Rancière calls the distribution of the sensible (Rancière, 2004, p.12). The boundary between text and image is a fulcrum where various political hierarchies are staged: between rational and irrational, reality and simulacra, erudite and popular, literacy and illiteracy, male and female, or adult and child.

We are particularly interested in the relationship between text and image in the context of graphic design. Throughout the history of this discipline, we have encountered several moments where technological innovations have caused a blurring of the boundary between text and image, all of which were followed by iconoclastic periods where the primacy of text was once again reaffirmed. Examining these moments can help us understand how artificial intelligence is being reacted to and how it might be normalized in the future.

In this communication, we focus on transgressions on the border between text and image. It seems like a small distinction, but it allows us to take an informed look at the present. Many of the changes we are about to mention have become naturalized, which sometimes prevents us from being aware of the nature of their transgressions. So, on the one hand, the past can be seen as a precedent for the present moment, but the reverse is also possible: the present moment allows us to look at the past with new eyes.

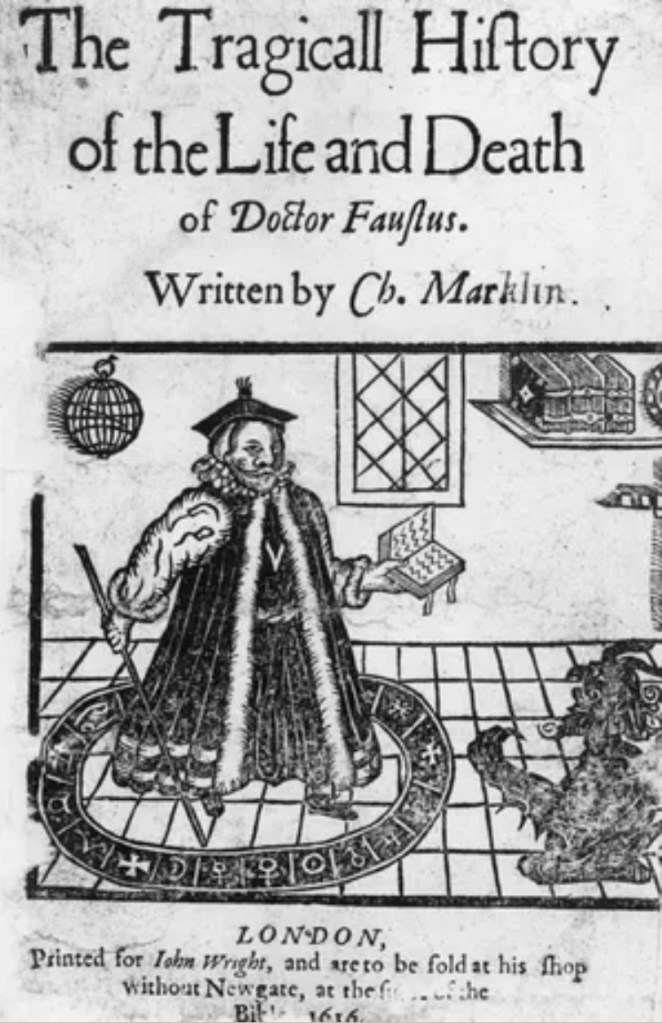

The printing press itself can be seen as a border between text and image. The practice of producing copies of the same book points to an idea of image or simulacrum that would not have gone unnoticed by the public of the time. Design historian Philip Meggs refers to the story, probably apocryphal, of how an associate of Gutenberg, Johann Fust, was accused of witchcraft when he tried to sell printed books in Paris. When his buyers compared the copies and discovered that they were almost perfect images of each other, Fust was forced to reveal the secret of his technique. The anecdote would supposedly serve as the basis for the story of Dr. Faust, who sold his soul to the devil (fig. 5) (Meggs, 1998, p. 67).

The ideia of the printed book as an image and simulacrum of the handwritten book is evident in this story. During the early years of the press, there was an attempt to regulate its exercise, which was also aimed at maintaining a hierarchy that sought to center power in those who dominated the text. This attempt took place not only through legal means but also through religion. Hans Belting describes how the Reformation, which coincided with the media revolution brought about by Gutenberg, abolished impure images and replaced them with the printed text of the Bible, translated into the vernacular, which could be owned by individual believers:

“The reader could touch the printed paper with his fingers, sentence by sentence, and let his eyes rest on the letters with the letters with the word of God […]. The act of reading purified the imagination and repelled ‘impure’ images.” (Belting, 2011, p.14)

The text as image of the press was thus placed in opposition to the pictorial image – but above it. The book, and text itself, become the primordial image that forgets its own iconic condition.

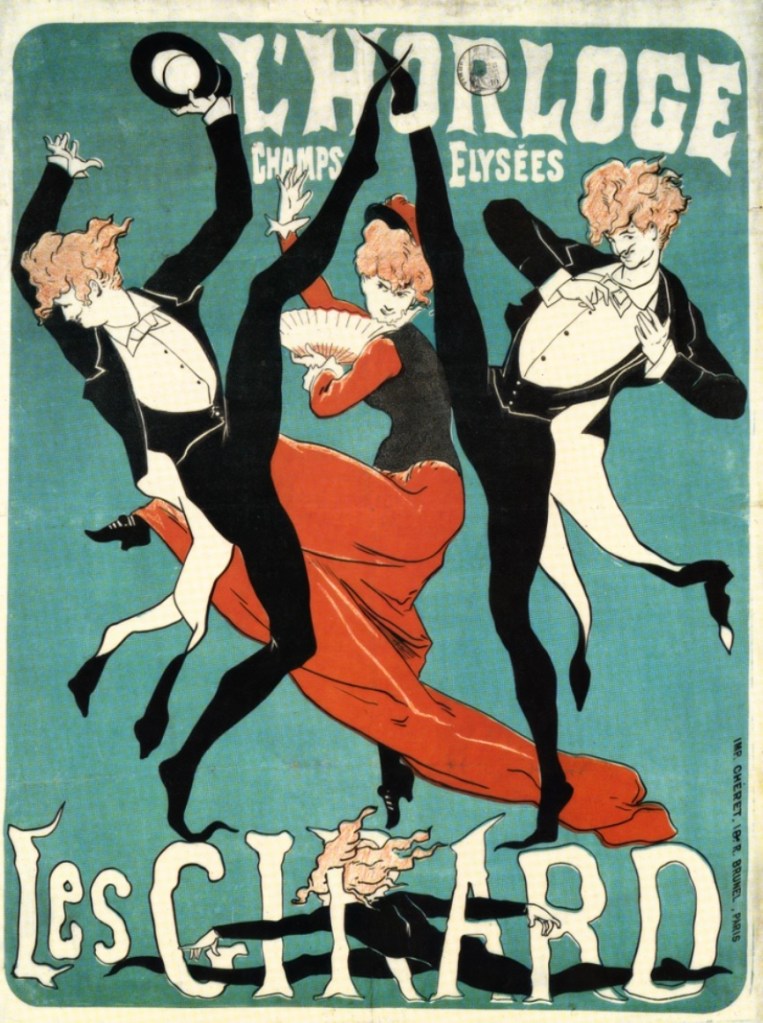

This kind of turnaround became recurrent whenever a new technology threatened the boundary between text and image. Lithography, invented by Alois Senenfelder in 1796, gave rise to modes of interaction between text and image that disrupted the typical hierarchy of traditional printing, where text was printed using lead characters and images using woodcuts. The lithographic artist could hand-draw letters at the same time and on the same plane as he drew the characters and environments without having to resort to typesetting. A founding example is Jules Chéret’s style of lithographic poster, where characters dance in the middle of the letters (fig. 6).

The architect and critic Adolf Loos harshly criticized this type of interaction. His justification shows traces of modernist formalism: typography should not be a portrait, i.e., an image of letters, but letters in themselves that are intended to be nothing more than printing ink on the two-dimensional surface of the page (Loos, 2004, 162). This subtle iconophobia marked modernism and found its most condensed expression in the old aphorism that the best design should be invisible. Under this motto, the New Traditionalism movement circumvented the Dadaist typographic collages or Moholy-Nagy’s experiments where typography and image merged in what it called Typophoto (fig. 7) (Moholy-Nagy, 1969, p.38). Much later, in the 1970s, lithography would become the dominant printing mode in its offset form, making lead typography obsolete. However, the rules of typesetting that ensured the integrity and primacy of the text had already been reinstated as an ethic and no longer as a technical imperative.

It should be noted that the primacy of the text was ensured by establishing moral precepts that opposed the utilitarianism of the text to the superficiality of the image. The emphasis on legibility was not just ensuring quick and efficient reading but equating text with functionality and utility. Discussions about legibility in the design field — almost always removed from any empirical data —, impose the presence and hierarchical ascendancy of the text over the image under the pretext of ensuring that a particular work is legible.

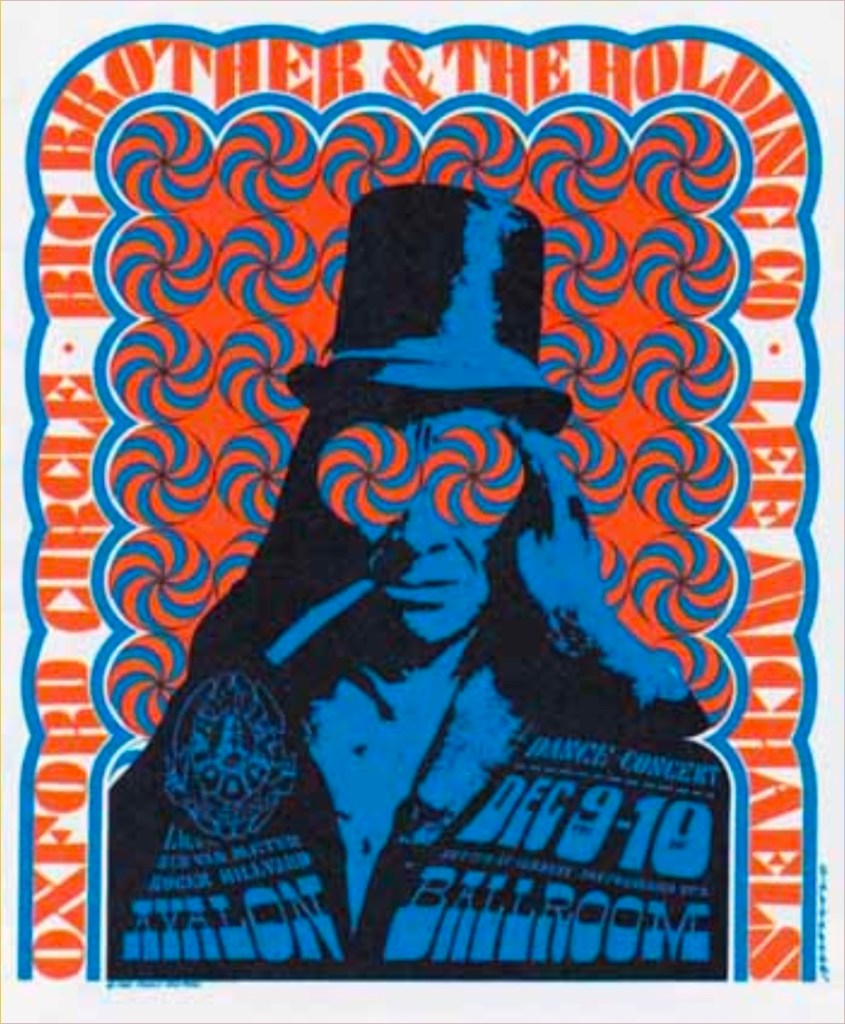

The deliberate illegibility of the text or its fusion with the image would become symbols of counter-culture, opposition to power, and utopianism. A good example is the psychedelic posters by Victor Moscoso (fig. 8) or Wes Wilson, where the text merges with the images and the background itself.

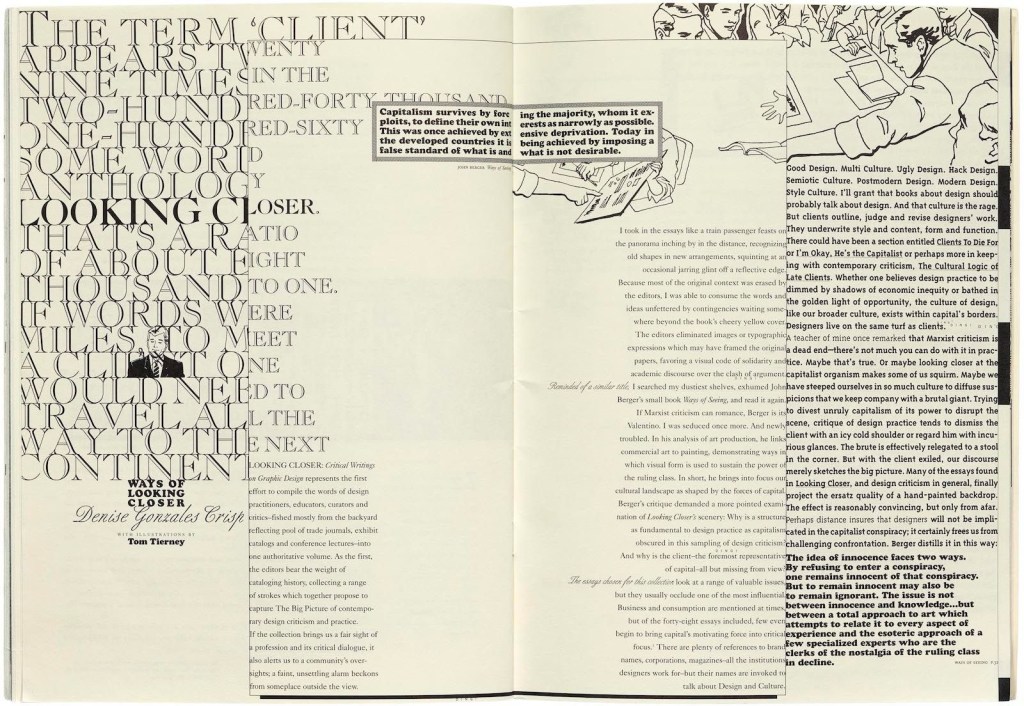

The personal computer would make typography even more accessible in the 1980s. It was a new technology with no material or technical separation between image and text, reducing both to digital bits. This lack of separation supported a series of experiments where typography and image merged. Emigre magazine (1985 – 2005) (fig. 9) is a prime example. The controversy surrounding this type of graphic design would become known as the “Legibility Wars” (Heller, 2016) — the name shows how these new ideas were evaluated through the bias of the text’s integrity (and centrality). In the end, the traditional hierarchies, based on a clear division between text and image, were reinstated and even gained ground. Shortly before it ended in 2005, Emigre became a text-based magazine laid out like a classic paperback.

The years that followed only deepened the textual turn in design. AI is a new shake-up of the boundaries between text and image in this context. Firstly, because it literally allows images to be created out of text. Secondly, it also spontaneously generates text when creating images (fig. 10).

Once again, it is possible to glimpse a future where text and image merge in new configurations. However, it is more likely that hierarchies will be re-established in this new medium through new criteria of taste and new imperatives of professional ethics. A hierarchy of taste is already palpable between images produced by free platforms like Bing and paid ones like Midjourney AI, or between the latter and the “invisible” use of artificial intelligence for processing and creating images in Adobe applications. While many designers react viscerally to this technology in its publicly accessible form, they accept it as part of their tools.

The likely result is that generative AI will become synonymous with amateur and vernacular imagery — as has happened with memes. Eventually, designers will appropriate the formalisms of this type of expression, using them to express transgression, popular expression, and even political intervention.

Presented as “Generative AI and the fear of images — Looking for clues about the future of artificial intelligence in iconophobic reactions to lithography and desktop publishing” in the “Towards an Automated Art” Internacional Conference, Nova FCSH, 24.05.2024

Bibliography

Belting, Hans. 2011. A Verdadeira Imagem. Porto: Dafne Editora.

Bredekamp, Horst. 2018. Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Dewdney, Andrew. 2021. Forget Photography. Londres: Goldsmiths Press.

Farocki, Harun. 2003. Erkennen und Verfolgen. Alemanha.

Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Heller, Steven. 2016. “Lost and Found in Translation – Revisiting the So-Called “Legibility Wars” of the ’80s and ’90s.” Print, Fall 2016, 58–63.

Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo. 1969. Painting Photography Film. London: Lund Humphries.

Jurgenson, Nathan. 2019. The Social Photo – On Photography and Media. London: Verso Books.

Loos, Adolf. 2004. Ornamento e Crime. Lisboa: Cotovia.

Marshall McLuhan, Quentin Fiore. 1968. War and Peace in the Global Village. New York: Bantam Books.

Meggs, Philip B. 1998. A History of Graphic Design. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 2005. What Do Pictures Want? Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo. 1969. Painting Photography Film. London: Lund.

Ong, Walter J. 2004. Orality and Literacy. London: Routledge.

Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. New York: Continuum.

Steyerl, Hito. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Stoichita, Victor. 2011. O Efeito Pigmalião. Porto: KKYM.

Zylinska, Joanna. 2017. Nonhuman Photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Leave a comment